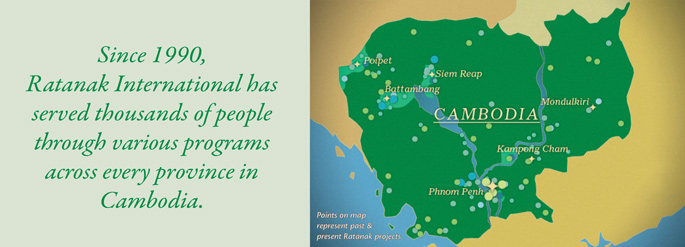

After five years of fighting, the civil war was finally over. The Khmer Rouge had won, defeating the US-backed republican regime led by General Lon Nol. The people were ecstatic, lining the streets of Phnom Penh, cheering for the Khmer Rouge as they came into the city. They were completely oblivious to what was ahead. For the next four years, the Khmer Rouge would establish a program of political, economic, religious and ethnic cleansing to completely remove every aspect of society that had been “tainted” by the West. Up to 3 million people died. Reaksa Himm is a survivor of “The Killing Fields”. His story is a powerful one- one marked by suffering, redemption and forgiveness. We are constantly blessed and inspired by his love for Christ and others, and it is indeed our privilege to work with him, a dear brother in Christ. Reaksa runs our Youth Development Program, a community center in a rural village which provides youth with access to computers, a library, physical education classes, counselling and mentoring.

40th Anniversary of the Unwanted Legacy

By Reaksa Himm

April 17th 2015 is the mark of the 40th anniversary of the legacy of the traumatic memories. The Khmer Communists made history with their great victory over capitalism. I was just a young boy. I remembered that evening in Siem Reap city. It was a bit quiet. Radio was broadcasting that Phnom Penh had been captured by the Khmer Rouge army. At that point, I remembered that my parents were saying that the war was over. They said, “Our country will be santrane—“PEACE.” Cambodian people were thinking that they would live peacefully as they had for centuries, the sounds of war would disappear and life would be happy again. Santrane actually never came. In fact, Cambodia slipped into the hell of the Killing Fields.

A few days after April 17th 1975, our family, like many others, was forced to leave our home when the Khmer Rouge came to power. We were taken captives and set to laboring in the countryside. Working hard from dawn to dusk with very little to eat and nowhere comfortable to spend the night, we became exhausted, demoralized and filled with despair. We lived under a regime of terror where the smallest act of disobedience to the soldiers or old liberated people brought death. After two years of this dreadful existence we were all starving. I watched helplessly as my friends gradually died of starvation. Their relatives were too weak to carry their emaciated corpses to a grave.

One memory I cannot erase was when my younger brother, who was only ten years old, was wrongly accused of stealing some corn. The evil chlops tied his hands behind his back and beat him unmercifully. They kicked him in the face so many times that he was unrecognizable. As I stood by helplessly, I wanted God to take away my life, because the pain of seeing my brother suffer like this was unbearable. I would rather they had tortured me than him. My parents were also unable to do anything, as even one word from any of us would have meant death. My father was overpowered by speechless anger and my mother was equally distraught. My poor brother was then dragged round the village to show what would happen to anyone else who stole or disobeyed the angkar loeu s’ brutal rule in any other way.

They repeated the same kind of torture on one of my older brothers and all of us began to lose any hope of life. Indeed we all wanted to die. I was enraged by the injustice and angry with God, Buddha and the evil chlops. If I had had a gun I would have killed them immediately. Anger and revenge burned in my heart with an intensity that gave me deep pain. When I went to bed, I could not sleep and I despaired that any of us would ever get out of this horror alive. Why was this happening to my entire family? I cried to God to stop all this evil but he did not hear my cry. My mother prayed to Buddha but there was no answer. Death seemed inevitable, whether by starvation or execution at the hands of these evil chlops.

No one heard our cry for justice. We were victims whose every aspect of life was subject to the Khmer Rouge’s torture. They could do whatever they wanted; we were their pawns in a deadly game. Their justice system turned on the head of a hoe. For us, true justice was dead. Defenseless, helpless and very weak, we were like chickens in a cage that wait to be slaughtered for food. We were not sure when it would be our turn and that was the source of our despair. There was nothing we could do but to obey their evil law. We could not run anywhere. In a jail without walls, we were the victims of an evil that had no boundaries. We could not die instantly, but at last we realized that this terrible existence was soon to end.

I went out early one morning to fetch some water and saw the chlops sharpening their knives and axes. I ran back and called my father, “Papa, I saw the chlops sharpening their knives and axes. I am afraid that they are going to kill us this morning.” My father was shocked to hear this and he opened his eyes wider than I had ever seen before. It was a sign of shock and despair. He did not speak at all but I could tell that, like me, he had become very desperate. I fed my youngest brother and dressed him, then a young teenager chlop came up to our house. Now I knew for sure that something terrible was about to happen to us. He came to see my father and said, “Mith bong [comrade brother], angkar loeu is inviting you to meet him in the shelter now.” My arms and legs shook with fear and I knew that something terrible would happen to my family.

My father responded, “I will be there in a few minutes. I need to get dressed first.” After he was dressed he came to tell me, “Reaksa, whatever happens to me today, I want you and your two older brothers who have been sent to work with the youth mobile team to kill these people for me.” With that, he went off and I trailed behind him to see what the angkar loeu would do to him. Right away a chlop arrested my father and bound his arms behind his back. One said to my father, “You are the khmang of the angkar loeu.” My father asked them, “What is wrong with me? I have not done anything wrong.” And then he was kicked in the stomach and they said, “You are the khmang of the angkar loeu. You served the American soldiers. We will destroy you today. If we keep you, we gain nothing, but if we kill you, we lose nothing.” When I heard that cruel pronouncement, I knew right away that they would certainly kill all of us. At that, I ran back to my younger brothers and sister right away. I told them, “Papa has been arrested. They are going to kill us today. I don’t know what to do now!” I could not stand still and I could not sit still. A great weakness came over me. As they realized that death would come soon, they started to tremble uncontrollably like me. Only Sopheak did not shake. He was sad, but he seemed to have no fear of dying. I could never have imagined how the fear of death could be so terrible. I hugged my younger brothers and sister but my weak hands could not hold onto them. They knew that I was terribly frightened and I could tell that they felt the same.

My father responded, “I will be there in a few minutes. I need to get dressed first.” After he was dressed he came to tell me, “Reaksa, whatever happens to me today, I want you and your two older brothers who have been sent to work with the youth mobile team to kill these people for me.” With that, he went off and I trailed behind him to see what the angkar loeu would do to him. Right away a chlop arrested my father and bound his arms behind his back. One said to my father, “You are the khmang of the angkar loeu.” My father asked them, “What is wrong with me? I have not done anything wrong.” And then he was kicked in the stomach and they said, “You are the khmang of the angkar loeu. You served the American soldiers. We will destroy you today. If we keep you, we gain nothing, but if we kill you, we lose nothing.” When I heard that cruel pronouncement, I knew right away that they would certainly kill all of us. At that, I ran back to my younger brothers and sister right away. I told them, “Papa has been arrested. They are going to kill us today. I don’t know what to do now!” I could not stand still and I could not sit still. A great weakness came over me. As they realized that death would come soon, they started to tremble uncontrollably like me. Only Sopheak did not shake. He was sad, but he seemed to have no fear of dying. I could never have imagined how the fear of death could be so terrible. I hugged my younger brothers and sister but my weak hands could not hold onto them. They knew that I was terribly frightened and I could tell that they felt the same.

Then, a chlop dragged my father back to the house and the others called us to come outside. They bound my hands behind my back but did not tie my younger brothers and sister. When they realized there was no one to carry my youngest brother, they unbound me so that I could carry him. Then they told us, “We will send you to school, because you are the khmang of the angkar loeu. Go with your father now!” They put us in an ox-cart and drove us from the village. We followed the Khmer Rouge who dragged my father along so that we had to watch his humiliation.

When we got into the jungle, there were other new liberated children with their fathers, some of whom we knew. I did not see their mothers nor did I see my mother. She and my older sister were probably still reaping in the field where they had gone early in the morning. I looked at the other children and could tell that they were frightened like me. I held on to my youngest brother but my arms could not stop trembling and it was very hard to sit on the ox-cart with him because I felt so weak.

Even then, I wanted to hit the chlop who was driving the ox-cart but I did not have anything to hit him with.

Besides what would I do with my brother then? If I hit the chlop I would not be able to kill him though I might hurt him. When I thought further about my younger brothers and sister who were with me, I decided to give up and wait patiently to be executed. The ox-cart took us about three kilometers from the village. One chlop came to stop the ox-cart a short distance away because they had not yet finished digging the grave. We waited there for a while. I got off the cart and carried my youngest brother to my father who knelt to kiss him. After he had kissed his youngest son, he kissed the rest of the children. I gave him a hug but he could not hug me in return because his arms were bound. He could not say anything either, instead I said, “Papa, I would like to thank you so much for being my father.” It was so painful to speak even those few words. I wanted to say more to him, but I could not. Feelings choked the words in my throat.

Faintly I heard my father say, “Reaksa, my heart is being torn to pieces; I have lived long enough but you, your brothers and your sisters are too young to die. They are so innocent. Look, look at your youngest brother; he does not know anything yet. He does not know that we are going to be killed soon. He is smiling and laughing. Does everybody else know that we are going to be killed?” “Yes, I told them after I saw the chlops arrest you in the meeting shelter.” My youngest sister cried, “Papa, I want to see Mak, I want to hug her, I want to give her a kiss and say good bye to her. Where is she?” My sister’s words choked my father, I could tell. He did not know how to answer her. I felt the same as my father and was almost speechless. Oh God! How could this happen to my family? I hugged my sister, holding her tightly in my arms and trying to encourage her by saying, “Mak will come soon.” That was all I could say. Five chlops were looking at us and laughing and I wished that I had a gun to kill them right away. Hurt and anger welled up in my soul. In contrast, Sopheak was calm and brave. He was not afraid of being killed for he had already tasted death. He seemed to know that after he was dead, he would not feel pain anymore. His arms and legs were not shaking like mine.

The other families were saying their farewells to one another. Were they as afraid as we were? I turned my attention from them for I just wanted to spend time with my family and talk to them before we died. My younger sister screamed to my father for help, “Papa, please help me! I am scared, PAPA!” My father did not answer my sister. He was a helpless man who was about to be killed. I could not imagine what he was thinking or feeling, but I sensed that his heart was rung with agony.

My father was now in front of the two wells that they had enlarged to be our graves. There were the chlops, wearing black uniforms and hand-made red Cambodian neck scarves, waiting for us to arrive. They kicked my father’s legs, forcing him to kneel. He turned his head to look at me and I saw them hack at his head with a hoe and then he fell into the grave with a terrible scream. I screamed too, “Where are you, God? Help us!” Screaming was useless.

Then one of the evil chlops jumped into the grave to finish off my father. I did not want to look at all, but I could not close my eyes; they captured every single act that was done to my father. The horrific scene before me filled my heart with a fire of rage that was intensified because I could do nothing to help him or the others. I thought I would die of suffocation before they hit me.

Then it was our turn. They called us to kneel in front of the grave and as I knelt down, Mao hit me from behind and I fell into the grave on top of my father who was not yet dead! I heard his last few breaths. Then there was nothing. My younger brothers, sister and others tumbled into the grave too, landing on top of me. Finally, they clubbed my baby brother. The first three times they struck him he screamed loudly, then they clubbed him once more and I didn’t hear him again. I was still conscious but I could not move. I knew that my siblings and the other children were not yet dead for the chlops jumped into the grave to chop wildly at us. In their frenzy, they mangled everybody with their axe but they missed me. After the chlops had finished their slashing spree, they climbed up out of the grave. I heard one of them say, “I think that one is not yet dead.” At whom was he pointing? I could not see because I was lying face down on my father’s body, covered by the bodies of my brothers and others but I found out very quickly. One chlop jumped down into the grave again to pull somebody off me and then he hit with the hoe once more but not hard enough to end my life. They thought that I was truly dead and did not slash at me as they had done to the others. If I had moved my legs or hands then, they would have finished me off. I could not move because of the weight of dead bodies lying on top of me.

They began to fill the grave but I heard someone say, “Don’t bury them now because there are some more khmangs to be destroyed.” Assuming that everybody was already dead, they left the grave open and went off to find other victims to feed to the earth. I had only one sensation then. I could taste death as blood flowed out through my nose and mouth, nearly choking me. I wanted to get out of there but could not move. Pain and panic took hold and I had to force myself to calm down. They would not fill in the grave right away and, if they left the grave soon, I might be able to get away. Five minutes after they were gone I tried to disentangle myself from the dead bodies. It took me almost half an hour to move out from under the dead bodies because I was so weak. After I had climbed out, I turned around to look at the bodies. Everyone was lying dead with throats slashed. My two younger brothers’ brains had spilled out. As for my father, his throat was slashed and split wide open. His eyes were open as though he were looking at me. He was already dead but his eyes were not closed so I stretched down and put my right hand on his face and closed his eyes.

After I had checked on everybody in the family, I sank down in despair, lying on top of those horribly mutilated bodies, waiting to be executed too. As I waited, I cried and cried until I had no more tears. I cried to God to hear me and also to Buddha. I cried until I lost consciousness. When I awakened, I knew that I did not want to run anywhere. I still remembered how my father had encouraged us to live together and to die together. I wanted them to come back and finish the job by executing me because my head was almost exploding with grief and emptiness. Young though I was, at that moment I realized that my life was meaningless. I felt as though I was swimming in a sea without sight of land. My only desire was to let them kill me; the pain was too much to bear and I didn’t want to live like this for the rest of my life.

After I had checked on everybody in the family, I sank down in despair, lying on top of those horribly mutilated bodies, waiting to be executed too. As I waited, I cried and cried until I had no more tears. I cried to God to hear me and also to Buddha. I cried until I lost consciousness. When I awakened, I knew that I did not want to run anywhere. I still remembered how my father had encouraged us to live together and to die together. I wanted them to come back and finish the job by executing me because my head was almost exploding with grief and emptiness. Young though I was, at that moment I realized that my life was meaningless. I felt as though I was swimming in a sea without sight of land. My only desire was to let them kill me; the pain was too much to bear and I didn’t want to live like this for the rest of my life.

I waited there for about an hour, but nobody came. Once more I climbed out of the grave and looked down at my family members lying dead in a pool of blood. I walked some meters away when I saw chlops appearing from the west and south, dragging other people towards the open grave. If I had waited at the grave for a few more minutes, the chlops would have captured me once again. Quickly I looked for a place in the woods to hide. I wanted to see who else they would kill. Suddenly, I saw my beloved mother and older sister stumbling towards the grave. Their faces were covered with a krama—Cambodian scarf and they were crying bitterly. My mouth opened to yell so my mother would turn round and I could see her face once more. If I yelled, maybe I could get their attention so they would come and kill me instead of my mother. No sound came and I felt strangely paralyzed. I tried again but it was as though a power was upon me and behind me, preventing me from crying out loud.

They clubbed my beloved mother and older sister and I saw them fall into the grave too. All I wished for at that moment was to tell my mother how much I loved her. I wished we had been able to say good-bye; at the same time, my heart burned with rage and I wanted to kill all these murderers right away in order to save my mother and sister but I was powerless and totally helpless. I couldn’t even scream at them to come and kill me. I watched as the chlops carelessly closed the grave and then left.

When the sun had almost set I crept out to the grave and pounded on it with my hands and hit it with my head. “Mak, please take me with you, take me with you. I do not want to live.” I called to my mother but she did not hear me. So finally, I bowed before the grave and made three promises to my family. “Mother, father, brothers, and sisters, as long as I live, I will avenge your deaths. If not, I will become a monk and if I cannot fulfill these two promises I won’t live in Cambodia anymore.”

After I made these promises, I realized I could not stay there. I began to think about what I needed to do to survive. Survival seemed impossible in the jungle, especially since there was no water to drink. I sat down and cried and cried and just wanted to die. Thirst and hunger overcame me because I had not had anything to drink or eat since my younger brother and I returned from fishing in the early morning. It was getting dark and I had never been in the jungle alone. I was afraid of wild animals that could easily eat me alive. I knew that if I slept on the ground close to the grave, the wild animals would kill me and eat me because they could smell the blood of the victims. I knew that I had to move away from the grave to find a place to sleep for the night.

About half a mile away I climbed a tree to get some rest. I will never forget the horror of that first night alone in the jungle as an inky darkness came down on everything. I heard something run along on the ground but couldn’t see what it was. As I despaired in this darkness, how I wished the sun would rise early and lighten this place of death! Mosquitoes bit me badly so I tried to keep moving all the time, but I was tired out and weak through lack of water and food. My neck was badly swollen from the blows I had received from the soldiers and I couldn’t breathe properly; it was as though something was blocked in my chest. Every time I moved pain shot through my chest and neck. I thought, this is because of my terrible karma and wondered about throwing myself from the tree so that I would die in peace and not suffer. But what if the fall did not kill me? I would suffer even more so I ended up hugging the tree trunk the whole night through.

I drank some dew in the early morning but it was not enough to quench my thirst and I was hungry so I returned to the jungle to search for food. After an hour, I found some bamboo shoots and broke them off for my lunch. They tasted disgusting but I had nothing else. I was lucky to get bamboo shoots because it was hard to find edible food in an unfamiliar place and I was afraid to go deeper into the jungle for I feared getting lost. After eating the shoots, I returned to the grave. I didn’t want to be there, but something drew me back. The spot filled me with horror but I had nowhere else to go and was reluctant to leave the bodies of my dear family. I spent three more nights in the forest then realized that if I was to survive I must find someone somewhere.

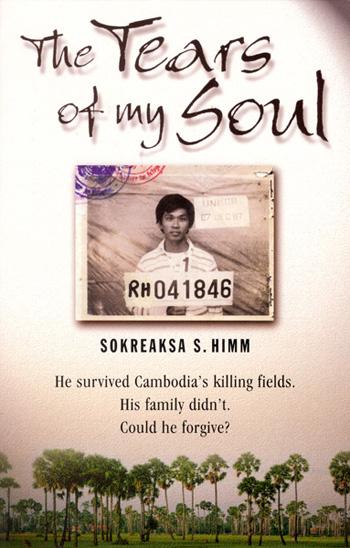

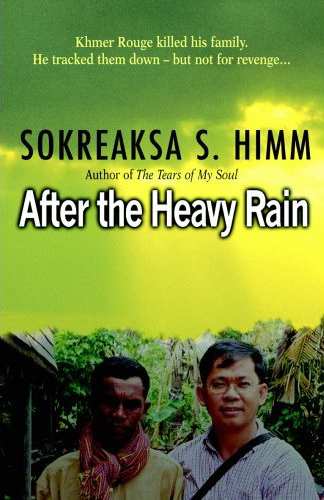

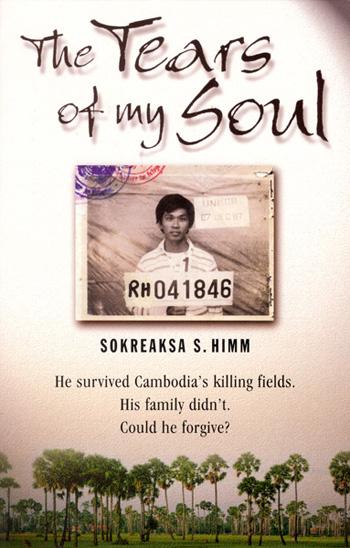

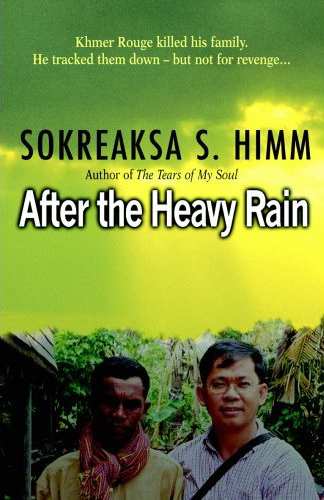

Put story in short, I survived. You can read my books, “The Tears of My Soul” and “After the Heavy Rain.”

You can also read about Reaksa’s story in A Healing Fire and Forgiveness: A Triumph Over Vengeance.

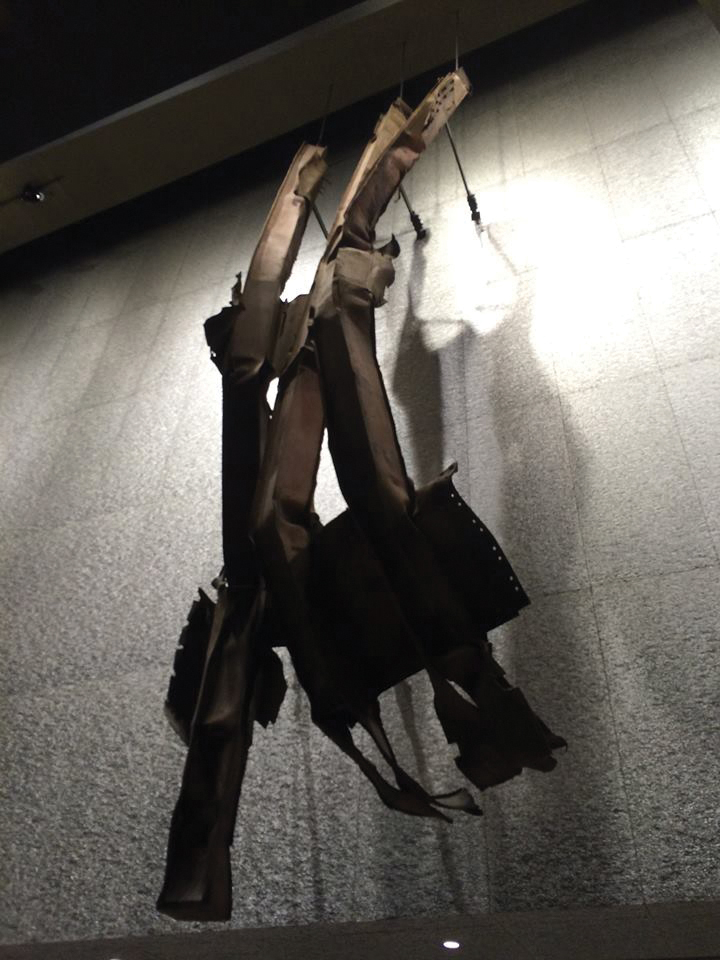

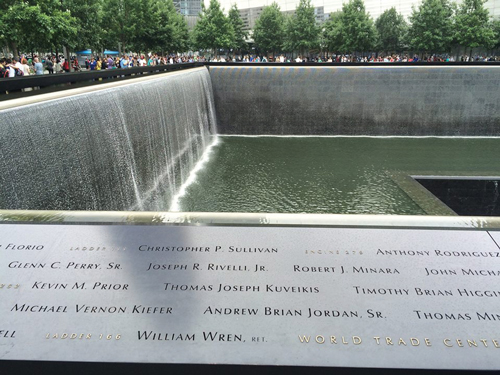

On a recent vacation to New York, Brian’s two worlds collided (he never stops thinking about Cambodia!). He met with Cambodian officials, went to the UN, and also visited “Ground Zero” for the first time. Walking into the 9/11 Memorial Museum, he was struck by a sense of familiarity. As a Canadian observer – an “outsider” as you will, to the events that have devastated so many Americans, he shares his personal reflections on a visit that became emotional and meaningful to him:

On a recent vacation to New York, Brian’s two worlds collided (he never stops thinking about Cambodia!). He met with Cambodian officials, went to the UN, and also visited “Ground Zero” for the first time. Walking into the 9/11 Memorial Museum, he was struck by a sense of familiarity. As a Canadian observer – an “outsider” as you will, to the events that have devastated so many Americans, he shares his personal reflections on a visit that became emotional and meaningful to him: I found myself mulling over the differences between the killing locations from the genocide in Cambodia versus 9/11 in New York. There is a quiet dignity given to those grieving in New York. Funding and resources have allowed this city to truly transform the World Trade Center location into a deeply respectful place. The understanding of the value of human life and the gravity of its loss is clearly present – a gift, I believe, given to this nation by its heritage of Christianity. This is contrasted by Cambodians, who do their best with few resources and even less understanding of the tragedy inflicted upon them.

I found myself mulling over the differences between the killing locations from the genocide in Cambodia versus 9/11 in New York. There is a quiet dignity given to those grieving in New York. Funding and resources have allowed this city to truly transform the World Trade Center location into a deeply respectful place. The understanding of the value of human life and the gravity of its loss is clearly present – a gift, I believe, given to this nation by its heritage of Christianity. This is contrasted by Cambodians, who do their best with few resources and even less understanding of the tragedy inflicted upon them.

My father responded, “I will be there in a few minutes. I need to get dressed first.” After he was dressed he came to tell me, “Reaksa, whatever happens to me today, I want you and your two older brothers who have been sent to work with the youth mobile team to kill these people for me.” With that, he went off and I trailed behind him to see what the angkar loeu would do to him. Right away a chlop arrested my father and bound his arms behind his back. One said to my father, “You are the khmang of the angkar loeu.” My father asked them, “What is wrong with me? I have not done anything wrong.” And then he was kicked in the stomach and they said, “You are the khmang of the angkar loeu. You served the American soldiers. We will destroy you today. If we keep you, we gain nothing, but if we kill you, we lose nothing.” When I heard that cruel pronouncement, I knew right away that they would certainly kill all of us. At that, I ran back to my younger brothers and sister right away. I told them, “Papa has been arrested. They are going to kill us today. I don’t know what to do now!” I could not stand still and I could not sit still. A great weakness came over me. As they realized that death would come soon, they started to tremble uncontrollably like me. Only Sopheak did not shake. He was sad, but he seemed to have no fear of dying. I could never have imagined how the fear of death could be so terrible. I hugged my younger brothers and sister but my weak hands could not hold onto them. They knew that I was terribly frightened and I could tell that they felt the same.

My father responded, “I will be there in a few minutes. I need to get dressed first.” After he was dressed he came to tell me, “Reaksa, whatever happens to me today, I want you and your two older brothers who have been sent to work with the youth mobile team to kill these people for me.” With that, he went off and I trailed behind him to see what the angkar loeu would do to him. Right away a chlop arrested my father and bound his arms behind his back. One said to my father, “You are the khmang of the angkar loeu.” My father asked them, “What is wrong with me? I have not done anything wrong.” And then he was kicked in the stomach and they said, “You are the khmang of the angkar loeu. You served the American soldiers. We will destroy you today. If we keep you, we gain nothing, but if we kill you, we lose nothing.” When I heard that cruel pronouncement, I knew right away that they would certainly kill all of us. At that, I ran back to my younger brothers and sister right away. I told them, “Papa has been arrested. They are going to kill us today. I don’t know what to do now!” I could not stand still and I could not sit still. A great weakness came over me. As they realized that death would come soon, they started to tremble uncontrollably like me. Only Sopheak did not shake. He was sad, but he seemed to have no fear of dying. I could never have imagined how the fear of death could be so terrible. I hugged my younger brothers and sister but my weak hands could not hold onto them. They knew that I was terribly frightened and I could tell that they felt the same. After I had checked on everybody in the family, I sank down in despair, lying on top of those horribly mutilated bodies, waiting to be executed too. As I waited, I cried and cried until I had no more tears. I cried to God to hear me and also to Buddha. I cried until I lost consciousness. When I awakened, I knew that I did not want to run anywhere. I still remembered how my father had encouraged us to live together and to die together. I wanted them to come back and finish the job by executing me because my head was almost exploding with grief and emptiness. Young though I was, at that moment I realized that my life was meaningless. I felt as though I was swimming in a sea without sight of land. My only desire was to let them kill me; the pain was too much to bear and I didn’t want to live like this for the rest of my life.

After I had checked on everybody in the family, I sank down in despair, lying on top of those horribly mutilated bodies, waiting to be executed too. As I waited, I cried and cried until I had no more tears. I cried to God to hear me and also to Buddha. I cried until I lost consciousness. When I awakened, I knew that I did not want to run anywhere. I still remembered how my father had encouraged us to live together and to die together. I wanted them to come back and finish the job by executing me because my head was almost exploding with grief and emptiness. Young though I was, at that moment I realized that my life was meaningless. I felt as though I was swimming in a sea without sight of land. My only desire was to let them kill me; the pain was too much to bear and I didn’t want to live like this for the rest of my life.